What Gives Art Value?

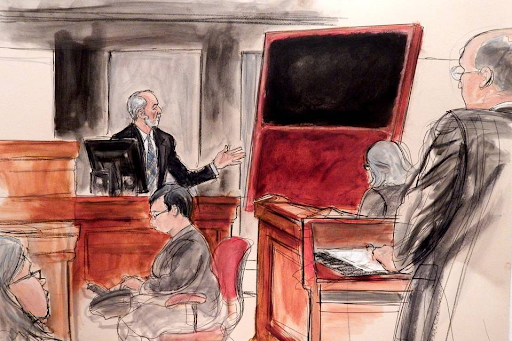

A courtroom sketch of the trial. Domenico De Sole gestures at the “Rothko.”

In the documentary “Made You Look,” an interviewee recounts a scene in a courtroom where experts debate the orientation of a painting made to imitate Mark Rothko: they aren’t sure which side of the painting is supposed to be the top. The story was presented with an ironic tone that is often used when discussing abstract art. It seems pretentious; experts can’t even tell what side is the top! What’s the point of the painting?

The case from which the scene is taken is one of art fraud. Ann Freedman, president of New York’s esteemed (at the time) Knoedler Gallery sold about 80 million dollars worth of faux abstract expressionist paintings, ostensibly by the likes of Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, and Robert Motherwell. Ms. Freedman maintained that she had been completely oblivious to the fact that the paintings, all sold to her by a woman named Glafira Rosales, were fake. Many of her buyers believed that Ms. Freedman was not as ignorant, or as innocent, as she claims. “Made You Look” chronicles the details of the criminal conspiracy: who made the forgeries and how, who bought them, who sold them, who falsified the provenance of the paintings, and the skepticism surrounding them? What interested me most, though, was the fundamental idea of art forgery.

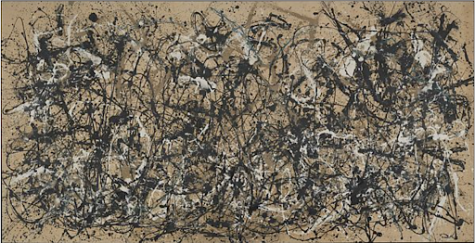

“Elegy to the Spanish Republic” (moma.org)

The problem with abstract expressionism and what makes it so easy to forge is that it is, well, abstract. The courtroom experts in the case could not even decide where the top of a supposedly masterpiece painting was. As much as I like Pollock’s work, it really is, in some sense, just paint splatters. So what makes Pollock’s splatters worth millions? It’s difficult to say. A lot of these paintings broke boundaries in what is considered art. They weren’t creating pictures anymore; the shapes and colors aimed to tap directly into the viewer’s brain to get directly to what the painter wanted to express, no longer cloaking the visceral reaction in something recognizable. The work is designed to get right to the viewer’s subconscious.

But does all of that matter? If you let a toddler loose with some paints, they could probably create something to fit right in with an abstract painting display. Pei-Shen Qian, the artist hired to forge the art, was able to trick some of the top experts on abstract expressionism into believing that they were works of various great masters. So was his art just as good? If not, then why not?

Eleanore and Domenico De Sole certainly seemed to think his art was on par with the masters’ when they first saw a forged Rothko for sale at the Knoedler Gallery. In the documentary, they said that they had liked one of his paintings so much that when Anne Freedman presented it to them they bought it for eight million dollars. When they heard the truth, though, they wanted nothing to do with the work. “Made You Look” shows the two of them with tears in their eyes, cursing the terrible injustice in the world. How tragic that the million dollar painting wasn’t made by someone famous!

Why did they buy it, and why did they react this way when they found out the truth? Obviously, it isn’t fair they were sold something under the false pretense that they were buying the work of an acknowledged master, and it makes sense for them to be upset. But they still had a painting they believed was of sufficient beauty and artistic value to be worth $8 million. Clearly, therefore, the bulk of the problem was simply that it was not actually made by Rothko. Their tears reveal that their primary motive in paying millions of dollars was not to own a painting they really liked but rather to have an 8 million dollar original Rothko.

Owning a painting because of the fame of the artist is fine, however taking the time to notice the artist’s intention is better. Context can elevate understanding of abstract art. One viewer might just see paint splotches, but if that same viewer learns that the artist made it as a gift to their lover after getting married, the splotches might appear a bit more like words in a love letter. By this logic, the value of abstract art would be the artist and the context. Considering such context, De Sole’s Rothko would be effectively worthless because it was not created in a fit of the artist’s passion.

But is context what makes the art important or meaningful? Isn’t that the opposite of the visceral subconscious reaction that is supposedly the foundation of abstract expressionism? If the art is good the impact should be felt regardless of the artist who made it and their story. The impact is what separates masterpieces from kindergarten art class (which I would like to clarify is still wonderful art). It’s the artist’s job to translate what they aim to express into the piece. There are millions of artists out there, but the ones who are revered are revered because they are able to communicate most effectively, profoundly, and memorably.

There wasn’t a story or a name behind the fakes (at least not a true one), but the visceral impact – and therefore the allure – was evidently there for them. Each piece went to the Knoedler Gallery with as little fictional context as Glafira Rosales could get away with. The possibility of what there could have been, though, was worth millions of dollars. Eleanore and Domenico De Sole bought a “Rothko” painting and as far as they knew a famous man had attempted to express something very important to him through it. Did the sight of it evoke something to them? Perhaps not really, seeing how easy it was for them to denounce it. Was owning something by Rothko merely a status symbol for them? Is their position any different from any other dealers? From museums? From mere viewers trying to appreciate art? In other words: Is my appreciation of art any more or less superficial than theirs?

These questions lead to even more questions about the nature and value of art itself. Is it still as meaningful when separated from its artist? If not, then is the art work good at all or just the artist? How is an artist recognized as “good” if his art is only good because it came from the artist? If art is meaningful apart from the artist, then what’s the difference between great art and a forgery or an amature’s work? Is the artistic value of a work even related to the economic value, or is art worth more than the price people are willing to pay to obtain it? These are questions that people have dedicated much time and talent to answer, without resolution as far as I can tell. I don’t have a clear answer either, but “Made You Look” made me wonder about these questions, which I thought were interesting enough to share with you. What is more, I think these questions are only going to get more complicated with the rise of AI generated art and non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”). People pay tons of money for “NFTs” that often lack visual impact and dismiss art made by computers, despite the uncanny and ethereal effects it can impart. When we are searching for the value, or lack thereof, in these new medias, maybe we can look back to this legendary case of art forgery to help us understand why people appreciate art.

by Lucy DeMeo, Arts and Entertainment Editor

24ldemeo@montroseschool.org