Does heat really rise?

shutterstock_700819048.jpg (5000×2992) (rd.com)

A photo of hot air balloons, which work because hot air rises.

It’s a hot summer day, and you’re stuck in a house with no air conditioning. If someone asked you to clean the attic, you’d be horrified. Why? Since the attic is at the top of the house, it will be hotter. You might be tempted to explain it with a simple “heat rises.” But does heat really rise?

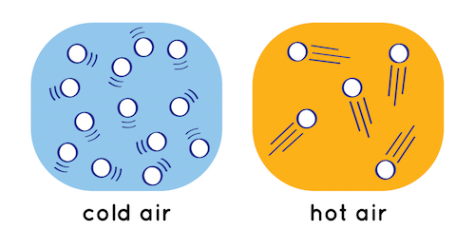

Technically, no. Heat is really a form of energy, not matter that can rise. But hot air, on the other hand, does rise. If you think back to IPS or chemistry, you may remember that as you heat a substance, its molecules move faster.

When the gas in the air is heated, its molecules move faster, bumping into each other more frequently and eventually moving farther apart as a result of those collisions. The warmer air then has a lower density, and you probably remember that substances of lower densities float on top of denser substances.

So basically, you can blame hot, less-dense air for your stifling attic.

By Hana Shinzawa ‘24, Co-Assistant Editor-in-Chief and Science Editor

24hshinzawa@montroseschool.org